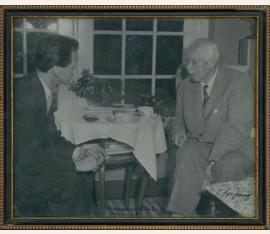

Psychologe und Psychiater (1875-1961). Photograph signed ("C. G. Jung") and inscribed "Arcana publicata vilescunt". N. p. 225 x 185 mm. Framed and glazed.

$ 10,145 / 9.500 €

(33265/BN28206)

Showing him in conversation with Hugh Burnett, the plinth of a bust showing behind him, at a tea-table. - The haunting phrase "Arcana Publicata Vilescunt", which may roughly be translated as "secret knowledge when published is made profane", is to be found on the title-page of the first edition of the "Chemical Wedding" of Christian Rosenkreutz (1616), an alchemical allegory by the early Rosicrucian and later Silesian father, Johann Valentin Andreae, and edited by the aptly-named Johann Friedrich Jung.

The teasing inscription on this photograph refers to the fact that it was Hugh Burnett's programme, "Face to Face", that brought Jung into contact with a mass audience for the first time. One of the viewers of the programme, Wolfgang Foges, contacted Burnett's interviewer, John Freeman, and asked him to contact Jung to sound him out about the possibility of writing a book explaining his views for the intelligent general reader rather than the specialist. Freeman conducted two interviews to this end with Jung, but was met with a firm but polite refusal. Jung then had a dream in which he was speaking in a public forum to 'a multitude of people who were listening to him with wrapt attention and understanding what he said'. When asked by Foges if he would reconsider, Jung agreed, on the condition that it consisted not just of his own writings but included essays by his closest followers, and was to be edited by Freeman. The result, which was to appear after Jung's death, was "Man and His Symbols", 1964 (cf. Deirdre Bair, Jung: A Biography [2004], pp. 619-620)..

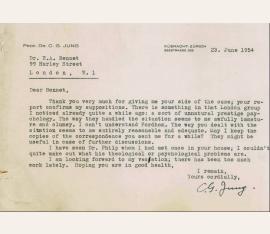

Psychologe und Psychiater (1875-1961). Typed letter signed ("C. G. Jung"). Küsnacht-Zürich. 23.06.1954. Large 8vo. 1 p. Addenda.

$ 9,077 / 8.500 €

(33269/BN28210)

To E. A. Bennet, about disputes among his London disciples: "[...] There is something in that London group I noticed already quite a while ago: a sort of unnatural prestige psychology. The way they handled the situation seems to me awfully immature and clumsy. I can't understand Fordham. The way you dealt with the situation seems to me entirely reasonable and adequate. May I keep the copies of the correspondence you sent me for a while? They might be useful in case of further discussions. I have seen Dr.

Philp whom I had met once in your house. I couldn't quite make out what his theological or psychological problems are [...]". - E. A. Bennet had been Jung's foremost advocate in England since the 1930s. - On headed paper; some slight edge damage. Includes a letter to Bennet by C. A. Meier, concerning the controversy Jung discusses in his letter, some letters of response from Bennet to Jung, Meier and others, typescripts of papers by Jung's associate, Toni Wolff, "Some Principles of Dream-Interpretation" (April 1934; 36 ff.) and "A Few Thoughts on the Process of Individuation in Women" (undated; 48 ff.), as well as an obituary brochure for Toni Wolff and some related material..